You could make an argument that horror is present in almost all books by Pakistani authors — if you were to consider the alarming levels of corruption, dirty politics and all-round degeneration of society as something disturbing enough to shock. Nevertheless, a Pakistani title that proudly caters only, and only, to the genre of horror, to the glorious prospect of generating fear of the dark and the supernatural in its readers, is a rare thing indeed.

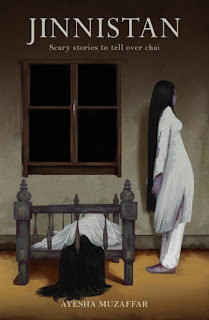

Ayesha Muzaffar’s Jinnistan: Scary Stories to Tell Over Chai — whose humble beginnings I first glimpsed on a popular Facebook readers’ group called Bookay (catering specifically to desi readers, and now, with growing popularity, to a larger international audience as well) — is one such title.At a visceral level, there is no doubt that the stories in this compilation are very scary indeed. Making the mistake of reading them in an empty house at night is not an experience I am likely to forget. Content in the knowledge that a book — unlike the truly horrifying medium that is the idiot box — couldn’t possibly be very frightening, I was forced to shut Jinnistan halfway through the fifth story. The only way to get through the whole 200 pages was to read it during the daytime, preferably while surrounded by other people.

There are some obvious reasons why Jinnistan manages to up the creep factor by a thousand. With a clear intent of presenting stories for a Pakistani audience, Muzaffar goes out of her way to add as many local references as possible. Everyone in her book lives in Karachi, Quetta, Lahore, Islamabad, or any of the many smaller cities and villages of Pakistan. The foods her characters like to cook and eat are parathas and qeema and jalebi, and enthusiastic descriptions of the absolute deliciousness of these items overflow in these tales. Everything — from the clothes to the lifestyles — is relatable to a person born and bred in Pakistan, meaning that, for a Pakistani reader, the stories feel very close to home and, thus, infinitely scarier.

It’s appreciable how the kind of love and affection Muzaffar shows for one’s own people in Jinnistan — even if most of her characters end up dead, mad or muted by fear — is slowly starting to become more commonplace in the narrative offerings from English-language authors of Pakistani origin. From stories based in London, New York or Afghanistan, we are shifting to tales based in the areas and surroundings in which many of us grew up. Given the urgent need to cure the lack of representation Pakistani children are bound to experience growing up, such stories only positively add to the conversation.

Even the overall tenor of the book — as suggested by the subtitle, which suggests cosy gatherings over steaming cups of the nation’s favourite beverage — evokes the idea of sleepovers with cousins where, with the curtains drawn and the lights dimmed, everyone pitches in with their own seven-minute versions of the man who met a female with feet turned backwards, or the haunted house their grandfather’s twice-removed cousin had once lived in.

At some places, however, the incessant referencing to local things can feel gratuitous and overdone. This is particularly true of moments when body parts are compared to mithai [sweetmeats], or when the reference feels too forced to flow smoothly within the narrative. A healthy amount of product placement is always helpful for creating a local effect, but overabundance can get irritating. This spillover occasionally occurs in the writing also, when the Urdu words (written as rough transliterations) seem interesting in the first instance, then begin to feel irksome.

On that note, over the years, as conversations about the intended audience of Pakistani writers has gained traction, the italicisation of Urdu words in novels written in English has been a contentious point for many in the literary community. Muzaffar — or rather, her editing/publishing team — seems to be a clear supporter of the side that states Urdu should be used freely and widely, without any italicisation or helpful glossary provided at the end for the confused English-only reader. This kind of unabashed self-acceptance of a readership among the local audience is a great show of confidence, and should hopefully give birth to more local talent that feels at ease straddling multiple languages. Unfortunately, Muzaffar sometimes take it too far, with not just sentences but whole chunks of text merging into Urdu for far too long, or into sequences that become awkward and senseless.

Overall, there is a sense that a keener editorial eye could have helped give the collection a bit more polish. From the choice of the stories to their placement, a stronger attempt at cutting out some tales that feel pointless and haphazard would have definitely helped create a smoother narrative. As it is, the storytelling style is very strongly reminiscent of spoken word tales, where there is less focus on direct dialogue and more on narrating a structure of events from beginning to climax and then conclusion. Fortunately for the reader, this doesn’t really take away from the overall enjoyment of the book itself, since it seems to have been done very purposefully.

At a thematic level, Muzaffar’s stories don’t seek to explain the unexplainable. There is no backstory given as to why certain houses are haunted, or whether a particularly violent supernatural entity is ever vanquished. What is enough is that we experience — along with the characters — the frisson of fear that heralds a presence at once unseen and malevolent.

Sometimes these forces are kind and helpful; in other cases they are jealous and petty. But in all situations, one thing remains true: human beings, with all their powers, must remember that they are not alone and, at any point in time, they can become the playthings of beings that are scarier, more vindictive and infinitely more powerful than us.

It is this idea that holds most of the collection together. With its definitive spotlight on the supernatural, we meet the usual bevy of horror-story bad guys, all intent on destroying human lives. As is the case with most stories in the horror genre, there is particular focus on women and children. Young females routinely get possessed, shadowed or kidnapped to serve as brides for nasty supernatural creatures. Children are usually the first ones to spot invisible friends, identify strangeness in their surroundings and act in manners alarming enough to frighten their elders.

As clichés go, Jinnistan is full of them. From the setting of the mithai shop (a particular favourite of tellers of desi horror tales) to the backward-turned feet of the churrails, we meet almost every trope that exists in the genre. However, this is easy enough to excuse, since the author very clearly does not seek to defend or explain a point of view. She is not attempting to subvert or challenge the genre. Hers are, in fact, the very basic form of horror stories. There is nothing new or original about any of them, except for the fact that they have not been gathered into a short story format before, and the fact that the author’s writing style makes them very scary indeed.

There are a few obvious flaws visible within the book. About 50 or so pages in, the tales start to sort of blend together. This might be an obvious drawback of the pattern followed: we meet the characters for only the length of time it takes for them to become involved in some strange and terrifying experience, before we are whisked off to meet the next bunch of random characters who will encounter a haunted house or an invisible entity.

Some stories veer into the mostly unexplainable realm of magic realism, while others make no sense whatsoever and seem to be quite accidental inclusions, as though the author tacked them on as an afterthought. The most unpleasant portion of the whole collection is the supremely uncomfortable element of mental illness and its overlap with possession. Pakistan has an upsetting lack of mental health awareness. It is one of those countries where people suffering from actual mental illnesses are exorcised in various tortuous ways by fake healers to cure a case of ‘ghost possession’. Thus it feels distasteful to read stories where this overlap occurs.

Still, Muzaffar’s stories ultimately do what they set out to do: create enough fear that the reader jumps at every odd noise. I avoided dark corners and shadowy rooms for a whole week after I was done with the book, so even with all the problematic aspects, Jinnistan is worth recommending. One can only hope that this leads to the emergence of a wonderful literary tradition that seeks to scare Subcontinental readers in new and wonderful ways.

***

This review was originally published in the weekly literary supplement Books and Authors on 15 November, 2020.